Part of me wishes we could redesign our curriculum. Not mine, not any specific schools’, but all of it—by pouring jelly beans out on the table. I think maybe what we teach is as important question as how students will learn it.

So some have the idea that mixing up traditional notions of “in school” learning with “virtual” learning can be a way to keep up the efficiency of teaching the ways that have sustained schooling for so long while also reducing the potential risk for infection of COVID-19. I realize the idea has real appeal: give students the face-to-face experience for all of its benefits, and combine that with the safety and security of learning from home.

I tend to side with science. There isn’t any pragmatic way to ascertain whether or not someone has been infected with COVID-19 aside from a test, and even the validity of those tests are in question. Without adequate protection or testing procedures, I wonder how we approach putting students in potential harm—and if not them—their extended families—by contracting COVID-19. As it has already been said, the safest approach is to assume everyone else has the virus. I’m an educator through and through, but a part of me can’t get past the fact that putting kids in school puts them at risk. Currently, COVID-19 is the leading disease cause of death in the United States and at the start of this year we didn’t even know it existed.

So let’s take a minute. Our health and the education of our students deserves, I think, a moment. Deep breaths, careful exhalation.

We each have to decide. What is more important? What lies in the balance is getting through a prescripted curriculum and exposure to a virus. Getting through the curriculum at any cost? The thing is, there are things unfolding around us that are quite different from any prescribed curriculum, but they’re real, and we all are being affected by them. “I can’t breathe” is something we just cannot ignore. Temperatures around the arctic circle just reached triple digits (in Fahrenheit, at least). Monuments are coming down, and there are debates on television about our country’s history. Life has changed a lot in just a year and I know it’s rough for many of us to deal with these changes. I have friends whose own children may not experience “a real college experience” and are upset. Others don’t want their kids to fall behind, whatever that means to you, when the fall comes for K-12 students. If we’re upset, even if they are too young to understand why their parents got laid off, or why they can’t socialize with friends, it’s going to have an impact on them.

I think the standards are changing before our eyes and I think we have an opportunity to understand this impact. There is inspiration for lessons around economics, health, science, politics, and social justice all around us. I think it’s a mistake to fret over how to cover an entire year’s published curriculum when there’s the potential for helping us better understand cope with what is happening now.

If you will entertain me for just a moment, I’d like you to imagine a large jar that holds jellybeans or gum balls (your choice). Each of the different colors, let’s say, represents a discipline, like math, language arts, music. And imagine if you could look inside our heads, walking down the street, we’d see that mix of colors all jumbled up. We’ve been through school and we carry with us all those little bits and pieces of that content knowledge.

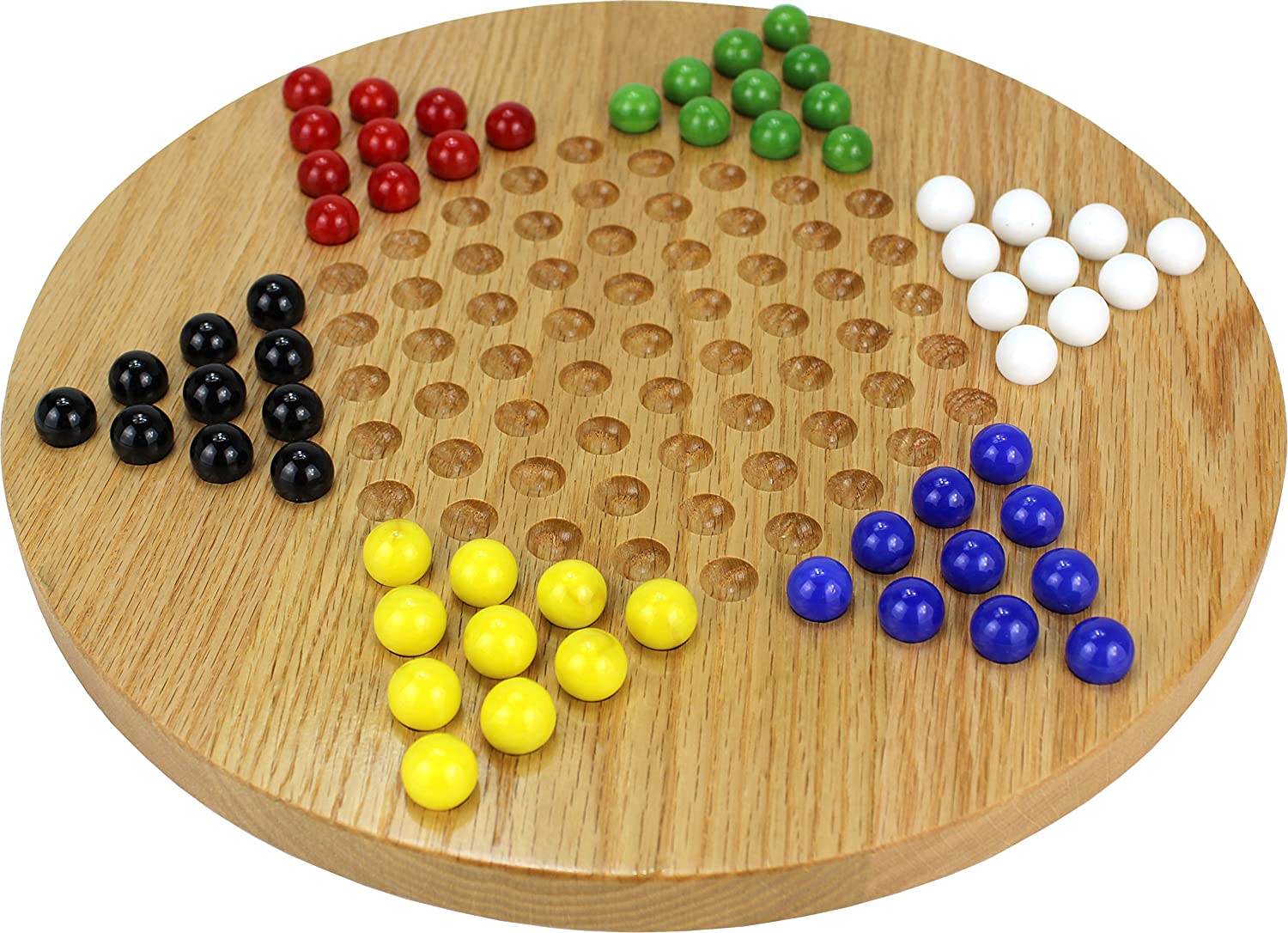

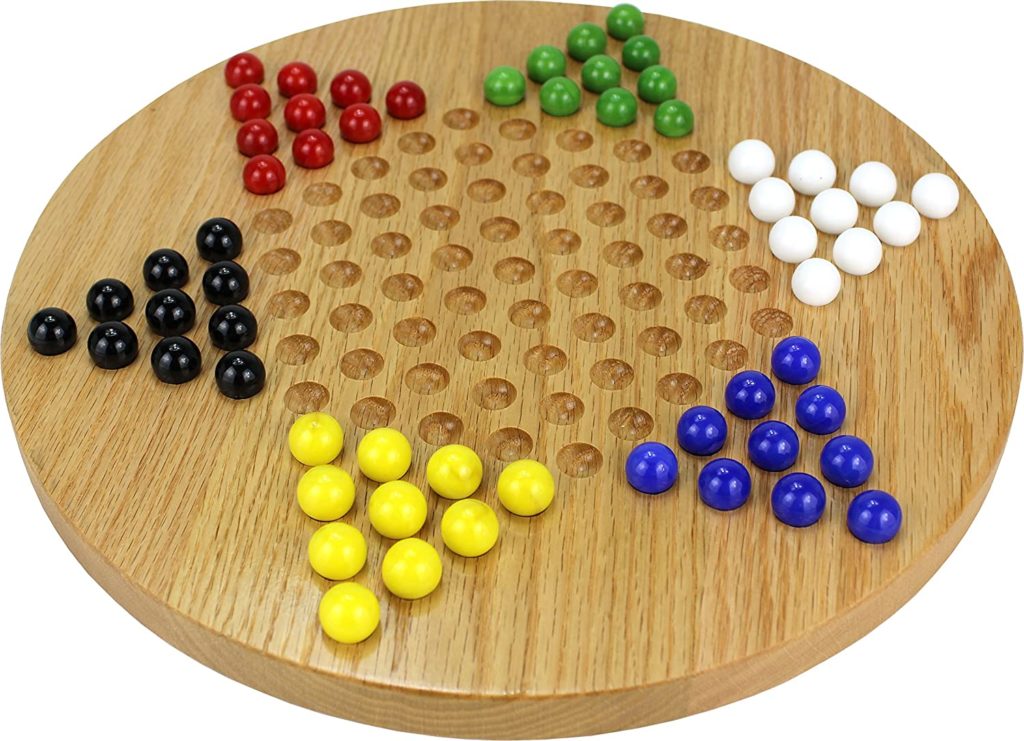

Except in school we like things organized because organization begets efficiency. The masterminds who work in curriculum and instruction take this jar of beans or gum balls and they pour it out onto the table. They use trays with divots (think of Chinese checkers) to organize content. Suddenly if we watch them long enough, all the beans become organized, into clusters, grouped by colors. Yes, occasionally a blue bean gets mixed in with the pink, but for the most part, each bean, representing different strands of knowledge to be earned by students, is scaffolded, sequenced, and then all that’s left to do, if we follow the plan, is to eat those beans in order.

Eating all of one color is bad for us, so we organize our days in school around eating the pink, then the yellow, then the blue. We take breaks for recess and lunch and go to it again. My apologies to secondary students, they get no recess, but instead a generous five minute break to find the next jelly bean snacking room.

I am hoping you see my point: we clean up life for kids – into small, digestible pieces of knowledge – and organize their day around providing snack-size sequences of beans to them. It’s not recommended we mix these beans up, but instead, they’re sequenced. Addition before subtraction, multiplication before division. Nouns and verbs come before adverbs and adjectives.

The most progressive schools in this country effectively have a different way to dispense the beans. It’s not that careful balance of sequence and such is a bad thing, but it also doesn’t mirror the realities of life. These schools build student knowledge through action, through construction, and in effect, they pour all the beans back into the jar, they shake it up, and the organization of beans isn’t neat, orderly, or color-coded. They’ll see patterns in those beans, and the projects students take on are multi-colored, not single-hued, and the different flavor combinations are to be celebrated.

The progressive educator smiles. “Isn’t this more like real life? Life is made up of all the colors, and they’re rarely so carefully clustered! It’s just like when we look inside your head, there aren’t compartments for each academic discipline, you’ve made sense of things, and the patterns and colors inside your head are what make you unique!”

We can take all the progressive education theorists of our generation, from Dewey to Papert, and they never had to posit the way we educate children against the threat of a killer disease that’s arrested life the way we know it.

I’m not suggesting we stop learning or that we stop teaching. But I am suggesting we slow down. We learned this past spring that if we want to teach from home, the pace has to slow down. Learning away from the structure of school requires time. And so does PBL and learning units designed around challenges. If we’re going to change schedules and how kids are grouped and who they see at school, we can do it based on how many desks fit in which rooms; or we can think about redesigning what learning can look like—perhaps further afield in the progressive spectrum—if we are going to do all this other work to try and make the schooling portion of our enterprise work.

I believe we corner ourselves when we set hard expectations around what teaching and learning has to look like. We corner ourselves when we base our schedules around work and productivity around daily periods of child care. And we corner ourselves when we make decisions out of a binary set of choices: virtual or face-to-face?

The truth is, digital technology can probably do a better job at keeping students within their zone of proximal development than an inexperienced teacher can. I’m not going to say it’s better, or that this solution is on the market today, but as a bold take-away, a computer can quickly assess what I know and what I don’t, it could measure my anxiety and focus, and it can recognize misunderstanding through questioning and provide remedial instructional interventions.

The solution, I think, is how we leverage digital tools in the hands of students to support learning when they cannot be at school. To connect them with their peers and their teachers. To challenge them with projects that mix up the colors of the beans a little, to not ignore what is going on around them. There is a fear, of course, in public education that straying too far away from the checkerboard is chaotic and dangerous. There will be a test. The patterns of beans will have to be replicated.

But right now—is that what is best? Or is there a way for us to address the needs of maintaining a semblance of schooling by mixing things up a bit, at least when it comes to curriculum?